Making the decision to outsource selected supply chain functions and processes to a Third Party Logistics (3PL) company can be challenging yet rewarding to the organization. Supply chain functions have grown increasingly complex with globalization, technology, and competition advancing at a rapid pace. Thoroughly examining the motivations, expectations, and justifications for outsourcing critical supply chain functionality enables companies to make effective decisions which generate incremental profitability and shareholder value. Careful consideration and analysis of cost factors, performance gaps, financial impact, and suitability for outsourcing yields superior outsourcing strategies and transition plans.

Outsourcing ultimately requires trust. Handing over various aspects of supply chain operations to a partner can be difficult for organizations that do not typically view their suppliers as cooperative partners. Ralph Waldo Emerson is credited with saying, “Trust men and they will be true to you; treat them greatly and they will show themselves great”. Entering a relationship with a 3PL company is like handing over your wallet to a business associate – Do you trust that your cash, credit cards, and family photos will be intact when you ask for it back? 3PL outsourcing is exactly like using a bank to handle your financial transaction management – you make deposits, you issue payment instructions, and you expect a perfect balance. With a 3PL contract – you issue goods to a carrier or receipts into a warehouse, you issue orders to ship or deliver to specific consignees, and you expect perfect execution and inventory balances. The difference lies in the physical realities of handling, storing, moving, and controlling physical products and their associated information over space and time. Trust is required and both parties to the relationship must do their part to build and maintain that trust in order to manage a successful operation.

Supply chain operations are evolving and advancing every year. For example, warehousing has evolved from the simple activity devoted primarily to material storage in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Adoption of just-in-time principles in the 1970’s and 1980’s drove smaller order sizes with increased frequency, lower inventory levels, and a greater need for order assembly activities occupying the space made available by inventory reductions. Leading companies reengineered warehouses into distribution centers and began rewarding distribution professionals with career advancement opportunities instead of perpetuating the perception of warehousing as a career killing profession. Adoption and growth of customer-driven designs, third-party logistics, postponement, mass customization, supply chain integration, and global logistics in the 1990’s added a variety of cross-docking and value-added service activities into supply chain operations. Logistics centers arose from distribution centers which combine customized labeling and packaging, kitting, international shipment preparation, customer-dedicated processes, and cross-docking with the traditional activities of storage and order assembly. The distinction between manufacturing, transportation, and warehousing activities is blurred in a logistics center. The margin for error is now near zero.

Supply chain management technologies have also significantly evolved during this time period. Large mainframes running financial applications supported by manual execution processes dominated the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. The advent of the PC, shared networks, and spreadsheets enabled better and faster analysis and the development of distributed processing systems for planning and execution. The internet’s growth form the late 90’s into the 2000’s has created an information explosion and wireless and mobile applications provide 24/7 information access to supply chain managers and customers. As a result, order cycles have steadily declined from months to weeks to days to hours. The pressures on the supply chain to respond and react continue to grow and the expertise required to effectively manage supply chain operations continues to increase.

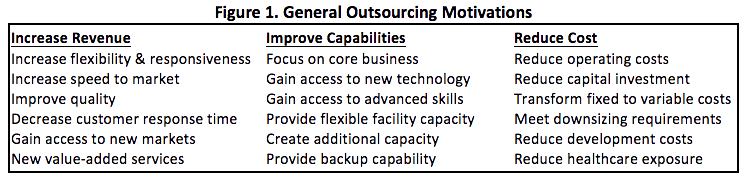

In response to these ever changing demands and increasing complexities, companies turn to outsourcing of supply chain operations including warehousing, transportation, materials planning, freight forwarding and reverse logistics. The general motivations for outsourcing these operations fall into three main categories: increase revenue, improve capabilities, and reduce cost. As illustrated in Figure 1, multiple motivations fall into each category.

While these and other valid and appropriate motivations drive outsourcing decisions, some companies use inappropriate reasons to justify their decision to outsource. Some companies choose to outsource simply due to lack of understanding of logistics processes. Lack of necessary skills may be a valid reason for outsourcing but companies should maintain enough knowledge of their logistics processes in order to effectively manage the outsourced relationship. Other companies justify their outsourcing decision on the ability to better identify the true cost of supply chain operations. Companies should first seek to understand their true logistics costs prior to outsourcing in order to make better decisions and build better relationships. Some companies want to off load the problems and issues associated with managing logistics operations. They mistakenly believe they can transfer the inherent problems and shift responsibility to a partner for resolution and not be involved with the detection, communication and decisions required to effectively resolve and reduce problems and performance issues. The result of this belief will manifest itself in frustration, anger, blame, and poor logistics performance. Desire to simply reduce headcount is another inappropriate outsourcing motivation as is the desire to simply reduce the asset base in order to achieve a short term improvement in the eyes of public investors. These results may be positive factors in the outsourcing decision but should not be the primary drivers. Outsourcing motivations will ultimately impact partner relationships and supply chain performance either positively or negatively.

Some companies never consider outsourcing or eliminate the strategic option of outsourcing too early in the supply chain strategy development cycle due to reasons that can be just as inaccurate or inappropriate as poor reasons to outsource. In-sourcing rationale may include an unconfirmed perception that cost will increase if an operation is outsourced. In many cases, this view is expressed by companies that do not know their true cost of supply chain operations. Another popular perception is that customer complaints will automatically increase due to decreases in overall service levels if an operation is outsourced. The belief is that the partner will not care about the business as much as internal employees do. This perception is based on the assumption that 3PL providers only care about their revenue which will not be the case if requirements are properly defined and contracts properly structured. Some companies have a strong perception that only they know their business well enough to effectively serve their customers and no other company can do it as well because their operation is unique. Their products and market offer may be truly unique but a qualified and experienced 3PL partner may actually have superior processes for order processing, storage, fulfillment, EDI, packing, labeling, and shipping which could actually better serve their customers. Another favorite rationale for in-sourcing is “we will lose control”. In reality, a well-structured 3PL agreement may yield increased control as 3PLs are operating under a customer centric, cost focused relationship in which all transactions are recorded, monitored and reported on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. The level of control an outsourcer has can actually be higher than an internally managed operation.

When selecting a strategy of outsourcing, a company must objectively evaluate its operations relative to outsourcing options. An outsourcing evaluation team should include members from the supply chain organization, finance or accounting, and sales. The evaluation and decision should consider cost analysis, performance gap analysis, financial opportunities, and suitability of operations for outsourcing. Cost analysis should include all of the operating costs associated with operations, including those costs that will be transferred to a service partner and those that will remain with the company. The performance gap analysis should include an objective assessment of company performance, strengths, and weaknesses supported by metrics and benchmarking comparisons if necessary. Outside expertise can be very useful for performance gap analysis in order to obtain objective results. Financial opportunities assessment includes reviews of fixed to variable cost conversions, potential cost of technology upgrades, matching cost to volumes fluctuations and benefits to the balance sheet or corporate capital structure. Suitability analysis refers to objectively evaluating process details in light of the performance gaps to determine the most likely candidates for enhancement through outsourcing.

Cost analysis is critical prior to engaging in an outsourcing process for logistics or supply chain operations. Companies should compare costs for each facility in each region and examine differences in costs, volume profiles, and cost per unit for both internal benchmarking and for comparison to outsourced alternatives. The cost of customer service including order processing, inquiry response, issue resolution, and electronic communications should be defined and documented. The costs may span multiple departments but are required in order to serve the customer and manage customer relationships. Cost of the inventory investment by location should be included in the analysis along with inventory related costs such as damages, lost, and obsolete inventory by location. Supply costs including procurement and inbound transportation may be impacted by outsourcing. Outbound transportation should be examined by location and mode as multiple opportunities may exist to reduce transportation costs. Warehousing costs for space, labor, and technology relative to activity profiles may expose additional cost savings opportunities.

Identifying and understanding all of the operational costs are important tasks to complete as an input for making the decision to outsource logistics operations. Recognizing regional differences and understanding the business or facility drivers that influence cost performance is important to developing functional requirements and evaluating future vendor proposals. Once all of the costs and identified and documented, the team should project which costs will be transferred to potential service providers and which will be retained after outsourcing for evaluation and planning purposes. Some providers may propose different levels of service or optional services that can transfer or defer different cost components. Cost analysis is an important component of the total outsourcing analysis and justification process.

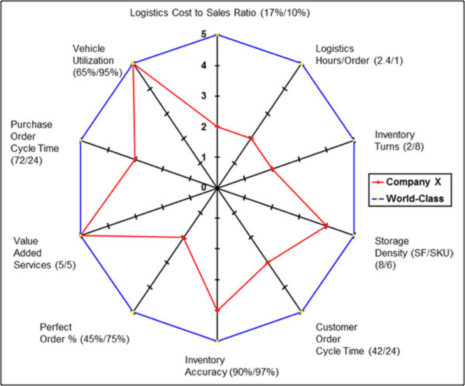

The logistics performance gap analysis is used to compare logistics key performance indicators with world-class indicators. The gaps enable assessment of strengths and weaknesses; identification of complementary logistics benchmarking partners; and development of cost-benefit justification of a world-class logistics initiative. Many companies must collect and summarize their operational performance data in order to develop many key performance indicators if they are not currently reporting them. Evaluating process attributes and their key cost and service metrics is required for the gap analysis. The team should assess each of the primary functions included in the cost analysis for performance gaps. In addition, the team should include the cost and gaps of the technology infrastructure in the analysis. Adequate technology support may be expensive to develop internally or may be already implemented with an opportunity to transfer transaction execution to a 3PL using internal systems. An example of a gap analysis summary is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Once the gaps are identified, the team should use them to better know the strengths and understand the weaknesses of the organization. The gap analysis enables the company to seek partners with strengths that can compensate for or complement the weaknesses or capability gaps which the company should strive to fill. A decision to outsource operations will then yield an evaluation requirement to leverage the expertise of potential partners to fill the most significant gaps in performance capability. Remember, that filling the gaps will take some time even for highly qualified partners as the company must adapt and develop internal processes to capitalize on the improved capabilities.

The team must evaluate financial opportunities relative to current cost factors, capital investment requirements for closing performance gaps, financial structure and objectives, volume variability and company risk tolerance. The analysis should consider current unit costs and the mix of fixed and variable costs and potential to convert fixed to variable cost. If gaps exist in technology capability, the team should estimate the capital investment required to adequately fill the technology gap and the time required for implementation. If the volume fluctuates significantly, conversion to variable cost will enable the company to more closely match period costs to volume resulting in a more stable cost per unit per period. Elimination of facility leases or sales of distribution facilities or fleet operations can have positive balance sheet impacts which can contribute extra savings or benefits to the outsourcing justification.

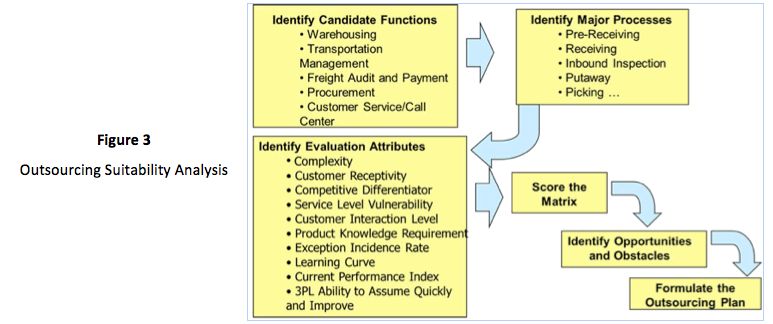

Outsourcing suitability analysis is summarized in figure 3 and involves an assessment of candidate functions, their major processes, and the company’s capabilities against a set of evaluation attributes that stratify elements such as criticality, competence, customer impact, complexity, and improvement capacity. Suitability analysis begins with developing matrices of the major outsourcing candidate functions such as warehousing, transportation management, order processing, freight audit & payment, specialized packaging & assembly, and returns & reverse logistics. Next identify the major processes within these functions that are required for successful execution. For example, major warehousing processes could include pre-receiving, inbound unloading, inbound inspection, putaway, order picking (various order types), outbound inspection, packing, outbound audit, manifesting, and shipping. The team should then develop a list of evaluation criteria that should include elements such as: complexity, customer receptivity, competitive differentiator, customer interaction level, product knowledge requirements, exception incidence rates, current performance gaps, and 3PL ability to assume quickly and improve. Team members should individually score the attributes for each major process. Once the scores are accumulated and summarized, the team should meet to review and reconcile the scores to create the list of the most easily and effectively outsourced processes and functions. During this meeting, the team should also identify the barriers and risks associated with the outsourcing decisions. Subsequent meetings are conducted to develop plans for overcoming the obstacles and mitigating risk in order to create the master outsourcing plan.

World-class logistics organizations partner with strategic providers of various logistics services including transportation management, transportation services, freight forwarding, customs brokerage, warehousing, logistics information systems, benchmarking, logistics consulting, and logistics professional education. The outsourcing decision for any one of these logistics services must be examined frequently (as the business and logistics environment is changing perpetually) and carefully (since it is typically more difficult to re-insource an activity). Outsourcing decisions should consider the following decision criteria to justify outsourcing a logistics activity. Consider logistics outsourcing if:

- Proven 3PL providers support your industry or support businesses with similar operational attributes AND

- Economies of scope and scale are available for a 3PL AND

- 3PLs potentially have a significant cost (-20%) and service advantage AND

- Outsourcing will fill operational performance gaps AND

- Outsourcing will not directly impact customer communications and relationships AND

- The 3PLs have a better warehouse management system or can effectively operate using your existing WMS

Once the decision to outsource is made, the team will begin the implementation process by creating the outsourcing plan and preliminary budgets and schedules.

As of September 8, 2020, Crimson & Co (formerly The Progress Group/TPG) has rebranded as Argon & Co following the successful merger with Argon Consulting in April 2018.