A new Trade Era

In a significant development, the United States and China have agreed to a 90-day pause in their trade war, reducing tariffs during this period. Announced on May 12, 2025, following negotiations in Geneva, the U.S. will lower tariffs on Chinese imports from 145% to 30%, while China will reduce its tariffs on U.S. goods from 125% to 10%[1] .

This pause offers short-term relief to businesses that have been under pressure from the tariffs. However, the underlying trade tensions remain unresolved, and the future beyond these 90-days is uncertain. Firms are advised to use this window to reassess and adapt their supply chain strategies, considering the potential for future disruptions.

China was hit hardest: cumulative U.S. duties on Chinese goods soared to effectively 145% [2]. Even long-standing exemptions were overturned, notably the de minimis rule allowing tariff-free small shipments under $800 was scrapped, slapping Chinese e-commerce exports with heavy fees [3].

Other Asian economies like Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Japan also faced targeted penalties beyond the 10% baseline. April 2025 marked a big shift in U.S. trade policy, one that directly challenged decades of global supply chain integration.

For the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region, this disruption cuts to the core. Long positioned as the world’s manufacturing engine – particularly for electronics, fashion, and industrial goods – Asia is now being forced to rapidly reconfigure its production networks.

This article examines how Trump’s 2025 tariff regime is impacting APAC’s key industries of; manufacturing, electronics, and fashion, with an eye on corporate profitability and the effect this is having on environmental, social, and governance (ESG).

From Trade War to ESG War?

The escalation triggered quick retaliation: China imposed tariffs of up to 125% on U.S. goods, basically cutting off many American exports. The World Economic Forum described April ‘25 as the moment when globalization “as we knew it” formally ended [4].

Critically, these trade disruptions have lots of ESG implications, many firms face profit margin pressure that could squeeze out investments in sustainable materials or renewable energy. The shift of production to new locations in pursuit of tariff relief brings environmental and social risks, from higher carbon footprints to labour rights concerns.

New pressures on ESG investment

Tariffs alter where and how products are made, with cascading effects on carbon emissions, resource use, and working conditions. They also impact corporate finances and risk calculations, which in turn affect ESG initiatives.

The 2025 U.S. tariffs have accelerated efforts by companies to diversify their supply chains. The “China+1” strategy – shifting production to countries like Vietnam or India – was already in motion, but recent events have impacted this.

This strategy is now facing resistance from U.S. policymakers. The U.S has made it clear that it views such re-routing as a form of circumvention. As a result, measures are being introduced to discourage firms from relocating Chinese operations to nearby countries, with the policy objective to bring manufacturing back to U.S. soil.

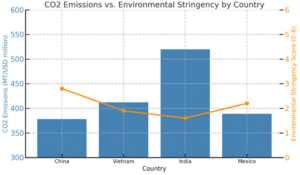

This adds complexity for decision-makers. Moving out of China may reduce direct tariff exposure, but it doesn’t eliminate risk. In fact, it can introduce new challenges. Countries like Vietnam and India have weaker environmental oversight and lower scores on the OECD’s Environmental Policy Stringency Index compared to China.

Figure 1: Environmental trade-offs of supply chain shifts – Countries like Vietnam and India tend to have higher CO₂ emissions per output and weaker environmental regulation stringency, compared to China. (graph from Asuene)

Real-world corporate data bears this out. Apple Inc. reported in its 2024 environmental disclosures that its supplier diversification (adding production in Vietnam and India) caused a temporary spike in Scope 3 emissions.

Shipping components to new assembly sites and ramping up new facilities led to higher transportation and energy use, pushing Apple’s supply chain carbon footprint upward even as it continued to pursue renewable energy and efficiency measures [5].

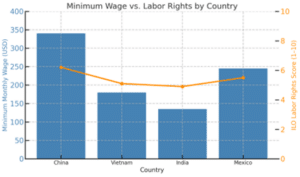

Figure 2: Social trade-offs of relocating production: Countries with lower tariffs like Vietnam and India often have lower minimum wages and labour rights scores compared to China, raising risks of labour exploitation if companies do not enforce strong standards (graph from Asuene).

The Trump 2025 tariff regime is not just redirecting supply chains, it’s disrupting deeply established networks across China and Asia. Firms now face pressure to unwind or duplicate operations that were built for scale, speed, and cost efficiency over decades.

The push to rebuild supply chains in the U.S. will likely come with higher costs, longer timelines, and incomplete short-term capacity. Meanwhile, environmental and social risks remain elevated, as shifting production, whether to less-regulated markets or immature domestic setups, makes sustainability harder to manage.

Manufacturing in Asia

Manufacturing remains the backbone of APAC economies, from steel to solar and electronics. The tariffs are increasing export costs and forcing companies to rethink long-standing production and supply strategies. Chinese metal producers, for instance, are closed off from the U.S. market by the 145% tariff [6], and now having to absorb the steep price disadvantages or redirect to other markets.

Many are turning to Southeast Asia or domestic projects. This could flood regional markets with excess steel at lower prices, benefiting buyers but potentially undercutting local steel industries (e.g. in Vietnam) and risking a race to the bottom on environmental standards if mills run harder to compensate for thin margins [7].

The solar supply chain illustrates the broader manufacturing disruption. China and Southeast Asia dominate global solar module production. In 2024, a U.S. investigation found that Chinese solar firms were routing products through factories in Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia to avoid existing tariffs.

The response in 2025 under Trump has been intense, with new tariffs on solar imports from those Southeast Asian countries, in some cases exceeding 3,500% – essentially an import ban for non-cooperating firms. For example, Cambodian-made panels by a non-cooperative company face 3,521% duties, and even major Chinese-linked firms like Jinko Solar (Malaysia) face tariffs of ~41% [8].

This has an ironic environmental impact: by penalizing the world’s cheapest solar producers, the U.S. risks raising solar panel prices domestically, potentially slowing the roll-out of clean energy installations. American solar developers have warned that these tariffs, although aimed at protecting U.S. solar manufacturing, will harm U.S. solar adoption by increasing costs and creating supply bottlenecks [9].

This highlights a conflict between industrial policy and climate goals: tariffs intended to bolster U.S. manufacturing of renewables are, in the short run, hampering the accessibility of those very renewable technologies. APAC manufacturers are strategizing to comply (for example, by proving no Chinese subsidy content in their panels) or else pivot to markets in Europe and the developing world where demand is robust, and tariffs are lower.

This recalibration of market priorities – focusing more on Asia, India, and Latin America instead of the U.S. is a strategic shift for Asian manufacturers [10] It might reduce reliance on the U.S. but could slow investments that were tied to serving it (including slowing any planned factory upgrades to meet higher environmental standards for that market).

Companies are adapting. Foxconn, for instance, has invested over US$3.2 billion in Vietnam, including a new US$380 million PCB plant, and is building chip assembly facilities in India. These moves reflect a broader regionalization strategy; Vietnam for East Asia, India for South Asia, Mexico for the Americas, and offer ESG gains through modern, energy-efficient designs and better worker housing [11] [12].

Electronics Industry

The electronics sector – spanning semiconductors and electrical components – relies heavily on rare minerals, energy-intensive processes, and labour-heavy assembly, while potentially generating substantial e-waste

After initially threatening blanket tariffs, the U.S rolled back duties on key tech products under pressure from U.S. industry. For China, even partial exemptions were seen as a win – a sign that the U.S. couldn’t fully decouple from Chinese electronics without harming its own tech sector. Beijing’s Ministry of Commerce called it a “small step” in correcting “wrong practices” and urging the U.S. to go further and remove all tariffs [13].

In practice, many electronics firms had already embarked on diversification during the 2018–2020 trade war and the pandemic. Here we can reference Apple again. By 2025, Apple had expanded production in India (for iPhones) and in Vietnam (for iPads, AirPods and soon MacBooks) [14].

his reflects a wider trend: high-tech manufacturing is now split across multiple hubs. India, Vietnam, and Mexico have all emerged as key bases for U.S.-bound assembly, a buffer against sanctions, tariffs, or supply chain disruptions tied to China [15].

But these shifts have ESG consequences. Moving production to multiple locations often increases emissions from transportation and complicates supply chain oversight. A laptop built across five countries instead of one may come with a larger carbon footprint unless logistics are tightly optimized.

For instance, Apple has been extending its Supplier Clean Energy Program to India and Vietnam (encouraging suppliers to use renewable power) [16]. This is crucial, because those countries currently have carbon-heavy grids (India and Vietnam rely a lot on coal). Without such efforts, shifting production could raise the carbon footprint per device. The circular economy aspect is also notable: with more assembly happening nearer to end-markets (like final assembly in India for India sales, or Mexico for U.S. sales), there is an opportunity to build recycling and e-waste processing locally.

Fashion under fire

No industry is feeling the impact of the tariffs as visibly as fashion. This sector operates on thin margins and complex global supply chains, often prioritizing speed and cost over all else.

China’s giants like Shein built empires on this model, largely enabled by the now revoked de minimis rule.

Previously, shipments under $800 could enter the U.S. duty-free. Shein exploited this by sending millions of small parcels directly to customers, avoiding tariffs altogether. In 2025, the U.S. closed this loophole for Chinese-origin goods, meaning a $5 t-shirt from Shein could now face duties exceeding its original price, making the ultra-low-cost model unsustainable.

To maintain U.S. market access, fast fashion firms are exploring workarounds: bulk shipping to U.S. warehouses, relocating production to third countries, or even establishing North American fulfilment centres. All of these raise costs and slow delivery, threatening the speed-price equation at the heart of fast fashion [17].

Ironically, tariffs may drive positive sustainability outcomes. Higher prices could curb overconsumption, nudging Gen Z consumers toward thrift and second-hand options. Fewer individual air shipments may also reduce emissions, especially if Shein consolidates freight. But if companies attempt to bypass tariffs by rerouting goods via third countries (e.g., China → Singapore → U.S.), logistics emissions could increase

Tariff risk is also reshaping sourcing. Cambodia saw a lot of Chinese-owned garment factories set up in recent years; however, it is now facing issues as well. The U.S. included Cambodia in the list of countries being used to circumvent tariffs (hence the solar tariff example). This shows the complexity: simply relocating production is not enough if rules-of-origin scrutiny increases. We might see more ** “Made in [other Asian country]” verification processes** to ensure Chinese inputs are not present.

The need to maintain profitability might conflict with sustainability investments: for instance, using sustainable materials (like organic cotton or recycled polyester) often costs more. If margins shrink, will companies continue to use them or revert to cheaper conventional materials?

As margins tighten, brands may be tempted to cut corners. But investor and stakeholder pressure are building. BlackRock and Vanguard, for example, issued 2024 stewardship guidance asking companies to disclose how they are managing ESG risks amid trade disruptions [18].

Brands that ignore labour standards or pull back from sustainability may face investor backlash, reputational damage, and even rating downgrades.

What are the three main things firms should be doing to respond?

Amid these industry impacts, companies are responding. The immediate priority has been damage control, maintaining profitability and supply continuity in the face of tariffs. But increasingly, a longer-term strategic recalibration is underway.

The “China+N” strategy, for a long time the key risk diversification play, is being reassessed. The question is no longer whether to diversify, but where. With Chinese-owned firms in Southeast Asia now also facing scrutiny and tariffs, the next “N” could be India, Mexico, the Middle East, or elsewhere. The decision now hinges on compliance credibility, cost-to-serve, and ESG compatibility – not just tariff avoidance.

- Diversifying supply chains with traceability: Leading firms are accelerating diversification, not only to spread risk, but to embed ESG considerations by region. For instance, renewable-energy-produced components from Country A might be paired with labour-intensive production in Country B with strong worker protections. This modular approach blends cost, compliance, and sustainability.

- The enabler is traceability. Companies are investing in digital supply chain mapping tools to track origin and ESG status in real time — from blockchain pilots to AI-driven traceability engines. These tools help both with tariff navigation (e.g., proving goods are made in Vietnam, not rerouted from China) and regulatory compliance (auditable ESG reporting, supplier certifications) [19].

- Cost management and ESG trade-offs: Many companies have undergone cost-cutting to offset tariff expenses; renegotiating supplier contracts, finding cheaper logistics. While some cuts potentially harm ESG initiatives (e.g. pausing a community project or a climate initiative), interestingly many firms are protecting core sustainability programs, likely due to stakeholder pressure.

- Sustainability-linked loans and bonds have continued to grow, reaching $340 billion globally in 2024 up from $122 billion in 2019 [20]. Companies know that if they abandon ESG targets, they could lose access to these favourable financing options. Thus, rather than cancelling climate targets, some firms are doubling down on efficiency to save money and meet those targets, essentially using the tariff crisis as a catalyst to eliminate waste.

- Strategic pricing and market shifts: Some companies are choosing to accept reduced margins in the short term to maintain market share. Others are targeting new markets where they can pass on some costs. Asian electronics and appliance brands, for example, are intensifying efforts in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where Western competitors and tariffs are weaker.

- This regional pivot won’t directly boost sustainability, but it may protect profitability and create headroom to fund ESG programs. Regional trade frameworks like RCEP also help; by facilitating intra-Asia commerce, they support localized production and shorten supply routes, which in turn reduce emissions and simplify ESG enforcement

Looking at the short-term vs long-term: In the short term, uncertainty dominates. Investment decisions are being deferred: Asia-Pacific M&A activity dropped 30% in Q1 2025, according to S&P Global, as companies put deals on hold to reassess exposure. This delays not only new capacity, but also ESG-linked upgrades tied to planned expansions. Companies remain in tactical mode, revising supplier lists, rerouting exports, and watching inflation as tariffs pass through to consumer prices [21].

Over the longer term, a new supply chain architecture is emerging. Instead of ultra-lean global models, companies are designing regionalized, shock-resilient, and ESG-aligned supply chains. One vision: Southeast Asia makes components, South Asia assembles, and the Middle East and Africa become new growth markets. This multi-polar model allows companies to spread risk and enforce ethical standards closer to source. As one industry analyst put it, “Asia is no longer just participating in globalization – it’s redefining it.” Companies that adapt early, by integrating tariff compliance with supply chain transparency and climate strategy, won’t just survive. They’ll lead [22].

Conclusion

The 2025 U.S. tariffs have not just disrupted Asia’s key industry sectors, they have exposed a deeper fault line between short-term and longer-term sustainability. Many companies have been forced into reactive cost-cutting, while others are using this pressure to rethink their operations more fundamentally.

What is clear is that the traditional model of cheap production, vast supply chains, and a ‘bolt on’ ESG, is not going to be as effective in the future. Firms that can restructure their supply bases with resilience and ESG built into their foundations will be better positioned to withstand not just tariffs, but whatever disruptions happen next.

Ultimately, the tariffs have triggered a reset. The organisations that see this clearly and act decisively, with a longer-term view will set the pace for the next decade of growth in Asia.